Pierre Boulez’s 100th anniversary is fully underway! Having had the privilege to work under Boulez’s guidance early in my career, it has been a special thrill now to be part of concerts dedicated to his music with the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra, at the Adelaide Festival, and at the Australian National Academy in Melbourne – most of them sold out and all extremely enthusiastically received!

And there is still the big one to come, a performance of a work which should not be missed this year: “Le Marteau sans maître” alongside “Structures II,” and the Second Piano Sonata, all on October 18 in the Helsinki Music Centre.

Helsinki Music Centre in time of the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra’s Boulez festivities in February 2025

Expanding Music’s Possibilities

Few listeners are indifferent to Boulez’ music. To be sure, there are those who hate it, while many adore it. Audiences certainly tend to love the live performances, we’ve seen this throughout the year. But what was Boulez’s mission, and where is the beauty in his music to be found?

“Schönberg is dead,” Boulez declared. He didn’t bother to mention the persistent hegemony of tonal music – his opinion on the lack of its contemporary relevance being obvious – but instead focused his criticism at the gurus of twelve-tone music whom he deemed prisoners of old forms, genres, and, in particular, rhythms in their music (just think of all the waltzes Schönberg composed). He recognized that by introducing dodecaphony they had started something important but left the work partially undone. What did he offer in place of the music of the old regime, which be proposed to strike down?

Arriving to a scene in ruins in post WWII Europe, the young Boulez wanted to demonstrate that music could do more than the maximalist sentiments and their reactive minimalist backlash of the previous generations. He wanted to re-think music’s possibilities in reflecting the subconsciousness and the interplay between rational and irrational. He proposed to do in music what Kandinsky and Klee had done in painting, what Mallarmé had done in poetry, and what Kafka and Joyce had done in literature – and for the next seven decades he lived up to his promise.

In Boulez’s music, we can experience musical structures that are spirals in which one concurrently senses past and future; sonorities which are both clear and blurred; fascinating speculations on temporality of music (such as questioning whether a beginning is really the beginning or rather just one of many possible windows to enter a work); and, central to the listening experience, harmonic vistas that expand the scope of our musical comprehension.

In country cafés where two mirrored walls ran parallel, one would enter and see oneself reflected into the infinity. Take one mirror away, and there is only a single reflection. I think the imagination is situated between irrational and rational invention just as between two mirrors: if it deprives itself either of the irrational or the rational, then it can see itself only once. – Pierre Boulez

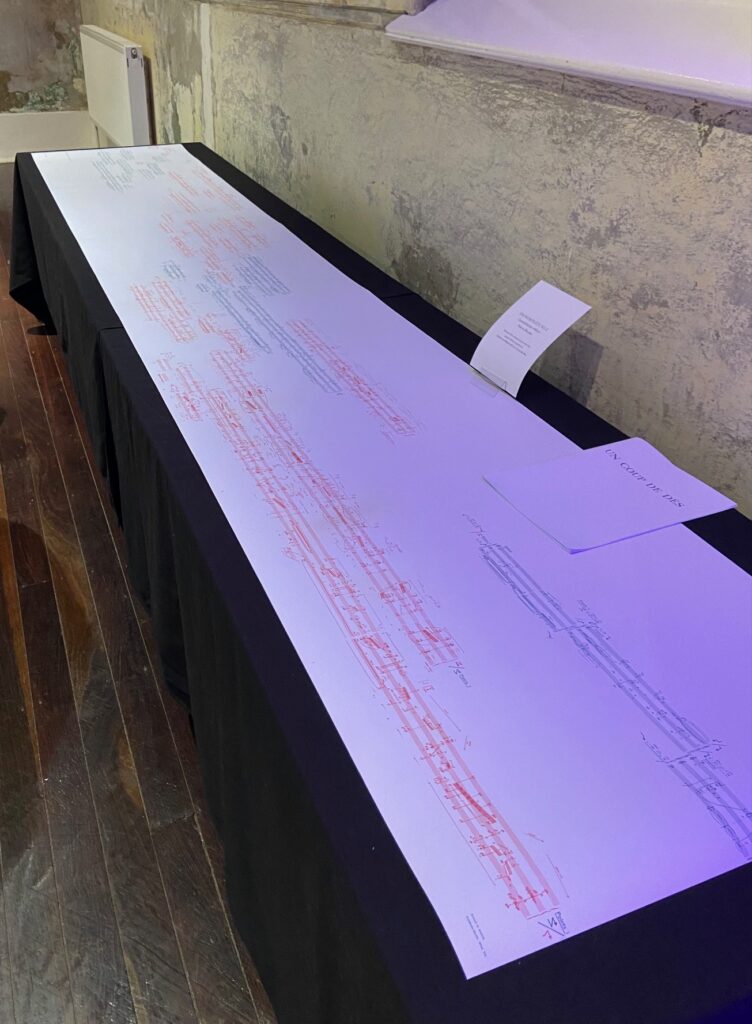

Stéphane Mallarmé’s poem directly inspired the structure of the 3rd Piano Sonata

The Hammer without a Master

“Le Marteau sans maître,” a cantata for alto voice and six instruments from 1954, is an endlessly fascinating play of relationships between the fixed and the flexible. Its instrumentation is novel and rich with intricate timbral relationships between the instruments. The voice (reciting poetry by René Char) connects with the flute as an instrument of breath; the flute links with the viola as an instrument able to sustain melodies; the viola pizzicatos discuss with the guitar and its plucked strings; the guitar and the vibraphone are resonators; the vibraphone and the xylorimba are instruments to be struck.

Like many of his French colleagues (painters as much as composers), Boulez in “Le Marteau” reached to exotic cultures for inspiration. He has pointed out that the vibraphone relates to the Balinese gamelan, the xylorimba to the music of Africa, and the guitar to the Japanese koto. Thus, in the words of Paul Griffiths, “Le Marteau is a pioneering essay in the music of the whole world.” Boulez didn’t attempt to exploit cultural artifacts, but rather create a mixture of sounds that looked outside of Europe – the continent which had done so much to try to destroy itself, along with a good deal of the rest of the world.

At the heart of Boulez’s music lies a tension between organization and freedom. It has been said that in “Le Marteau,” he attempted to do away with the composer’s fingerprint and set music free. His staves are filled with complicated and particular matrixes but often the word “libre” (indicating with freedom) written above. He said to be not interested in compositional tools like chance or electronics “as such,” but rather be curious about the new sounds they might yield. He felt very strongly that the way to musical freedom was through rigid labour which, however, should never be mechanic but always guided by instinct. He even was merciless toward thoses of his own compositions which he thought were “too concerned with theoretical concepts” and would without hesitation withdraw them. During the time of working on “Le Marteau,” his efforts were maximal and, listening to the work today, one can sense his achievement, as if Boulez had here come closest to the kind of freedom of expression he was fundamentally searching for.

Parallel to the aspirations for musical freedom ran political ones. Many of today’s concert goers remember well that when the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, it was Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony that was played on the site for the celebrating crowd. In the time of “Le Marteau” the early 1950s when Nazi Germany had fallen while the Soviet Union, another tyranny, was still ascendant, it was the young Pierre Boulez and his colleagues Stockhausen, Messiaen, and others with works like “Le Marteau” who were in the forefront of western Europe’s expression of modernism and quest for artistic freedom. With an humanitarian disaster barely a decade in the past, the most talented composers of the generation were boldly leading music in completely new directions, wanting to make sure that even in music past values would be completely washed away.

When on a walk, one can see the play of light on the leaves, if one looks at the leaves closely, one might be struck by the play of structures one to another. I have selected the example of leaves because I have seen for myself the relationship between one fixed arrangement of light the flexible arrangement of leaves. – Pierre Boulez

Troisième Sonate: Formant 3 – Constellation-Miroir

Legacy

Preparing and delivering performances of Boulez’s music this year, my colleagues and I have been guided by Boulez’s audacious vision, his uncompromising industry, and his optimistic belief in music that can renew itself and reveal more truths about universes, the micro as much as the macro. Playing this music is thoroughly satisfying and audiences love the live performances. The inspired conversations that took place at the Boulez Bar, set up for the one-day Boulez festival in Melbourne in April, as well as the endless and rapturous applause following the performance of “Sur Incises” that same night, were disarming testimonials of this, as were the demonstrations of sheer joy from performers of the Sonatine and “Messagesquisse,” young musicians who had immersed themselves in learning these extremely demanding works during months of preparation.

Boulez’s works we’ve performed this year include “Rituel,” the second and third Piano Sonatas, “Dérive,” Sonatine, “Initiale,” “Messagesquisse,” “Sur Incises,” and “Notations;” still to come: “Structures II” and “Le Marteau sans maître.” Few orchestras and festivals have taken on performing Boulez this year, the Finnish Radio Orchestra and the Adelaide Festival being wonderful exceptions.

Boulez has also been present in the airwaves and press. One of Australia’s most insightful classical music radio journalists, Andrew Ford, presented a riveting Boulez feature on ABC, and Iain Parsons dedicated the entire month of March on his show on PBM FM, “The Sound Barrier,” to Boulez’s music. There was also an intriguing article in the New York Times earlier this year, asking the important but too-soon-to-be answered question: “will Boulez’s music survive time?”

Young audience in front of the Boulez Bar at the Australian National Academy of Music

The Hammer without a Master – Boulez 100

Concert in the Helsinki Music Centre, Paavo Hall, Oct 18, 2025 at 4 pm

Program:

Claude Debussy: Excerpts from Études

Pierre Boulez: Le Marteau sans maître, Structures II, Piano Sonata No. 2

Performers:

Paavali Jumppanen & Emil Holmström, piano

Ismo Eskelinen, guitar

Yuki Koyama, flute

Atte Kilpeläinen, viola

Jerry Piipponen, Sampo Kuusisto, Alejandro Martín Agustín, percussions

Stephanie Lamprea, alto

Jeffrey Means, conductor

Bonjour, monsieur l’artiste!

Tulen uteliaana Boulez-festivaaliin Helsingin musiikkitalossa 18.10. En kuitenkaan huomannut etukäteen tilaisuuden kestoa. Minun on poistuttava jo väliajalla. Siksi julkenen kysyä mihin kellonaikaan se sijoittuu.

Kiitollisena tiedosta ( jota Musiikkitalon info ei löytänyt)

Irmeli Pyysalo

Hei,

Hienoa, että pääset kuulemaan Boulez-konsertin. Konsertissa on itse asiassa kaksi väliaikaa ja se loppuu klo 18:30. Aikataulu menee niin, että ensimmäisellä jaksolla kuullaan Boulezin teoksista Structures II, toisella Le Marteau sans maître ja viimeisellä 2. sonaatti. Jokaisella jaksolla kuullaan lisäksi yksi Debussyn etydi sekä hieman jutustelua teoksista. Väleissä on lyhyet 15 minuutin väliajat. Jaksot alkavat klo 16, n. klo 17 ja n. klo 18. Toivottavasti ehdit nauttimaan mahdollisimman monesta teoksesta!

Lämmin kiitos täsmällisistä tiedoista!